Winthrop Jacobs’ design patents

Who could have imagined that Winthrop Jacobsʼ carpet design would be a matter for the U.S. Supreme Court to decide? Or that the subject would become relevant again 150 years later in the smartphone patent lawsuits between Apple and Samsung?

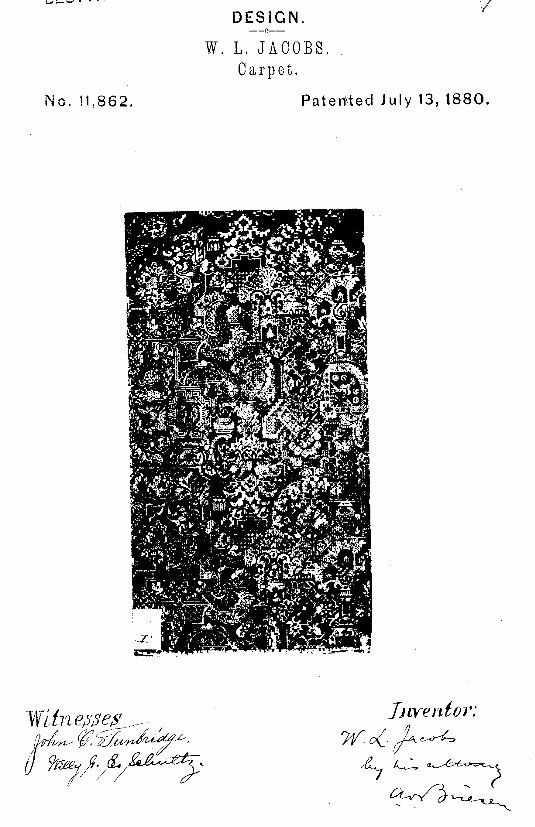

Itʼs improbable enough that Winthrop, the son of a Jersey City fruit broker, became a carpet designer at all. Yet we have more than a dozen design patent filings by Winthrop in the 1880s, with the rights assigned to the Hartford Carpet Co. or to other Connecticut and New York carpet mills.

The filings include a drawing of the design with a detailed description of each individual design element. A claim of ownership is made for the overall design and for each of the elements.

Mass manufacturing of rugs and carpets began in Connecticut in the mid 1800s, accelerated by the invention of the Bigelow broadloom. The Bigelow company merged with another company and became Hartford Carpet. Later, it did business as Bigelow. The issue at hand in the 1885 case that reached the Supreme Court involved a rival carpet company that had infringed on three of Hartfordʼs designs, including one by Winthrop Jacobs. Though there was no question of the infringement, the amount of damages to be assessed patents was at issue. Should the defendant forfeit the entire profits derived from selling the carpets, or only a fraction of the profits that resulted from the design.

The court ruled there was “no evidence as to the value which the designs contributed to the carpets,” and therefore no support for a share of the profits. The Court reversed the lower courtʼs entire profit awards and awarded nominal damages of six cents in each of the three cases. In response, a powerful Connecticut senator pushed Congress to enact legislation in 1887 that set a minimum of $250 for design patent infringements, thus protecting his home-state carpet industry.

The matter became an issue again in 2016 when Apple and Samsung were battling in the smartphone wars. Apple held a smartphone design patent for several human factor and user interface features. A lower court had ruled that Samsung should forfeit the entire profits from its infringing products, but the Supreme Court held, citing Dobson vs. Hartford, that the value of Samsungʼs phones was only partially due to the patented design features.